Carolingian Renaissance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three

As Pierre Riché points out, the expression "Carolingian Renaissance" does not imply that Western Europe was barbaric or obscurantist before the Carolingian era. The centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West did not see an abrupt disappearance of the ancient schools, from which emerged

As Pierre Riché points out, the expression "Carolingian Renaissance" does not imply that Western Europe was barbaric or obscurantist before the Carolingian era. The centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West did not see an abrupt disappearance of the ancient schools, from which emerged

To address these problems,

To address these problems,

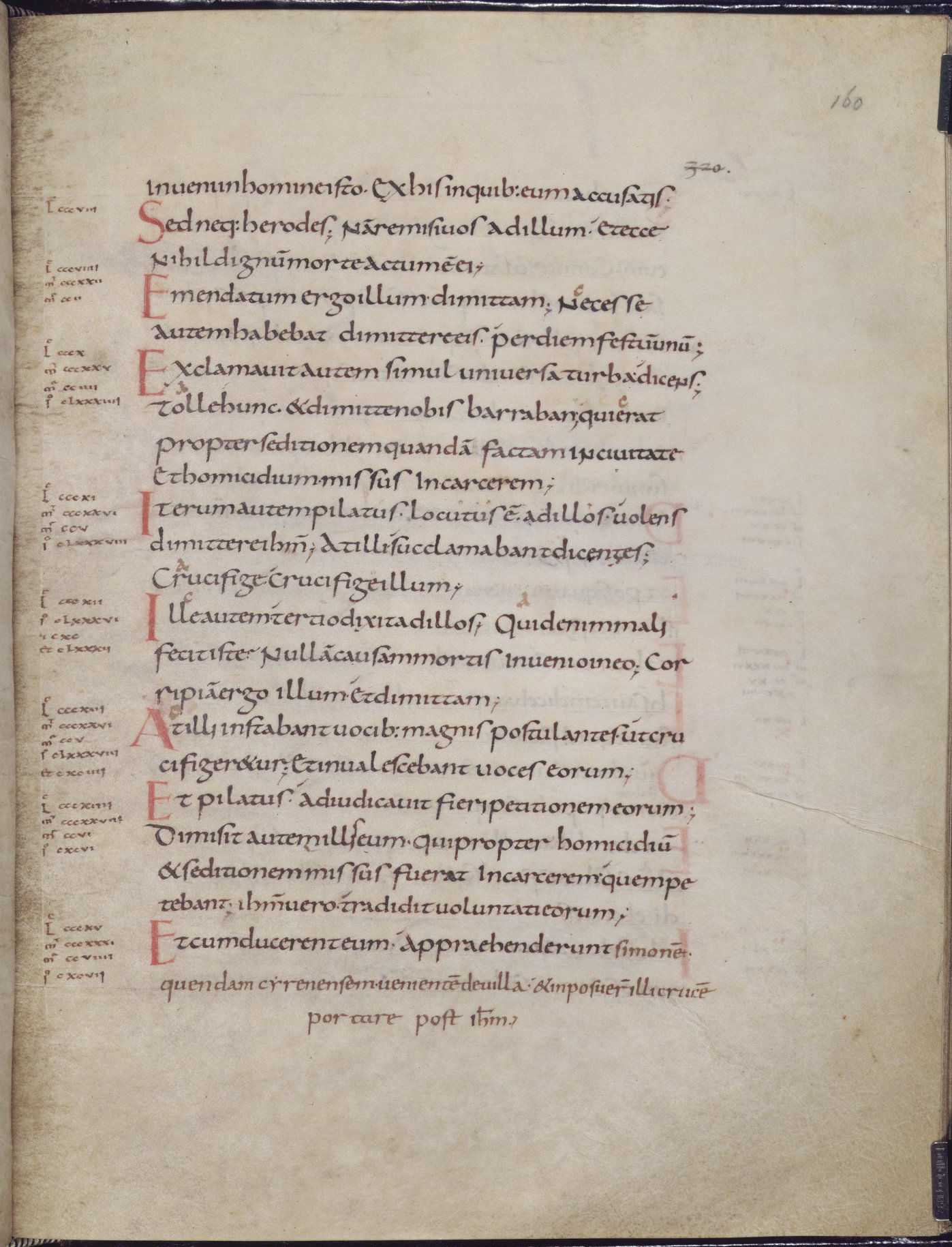

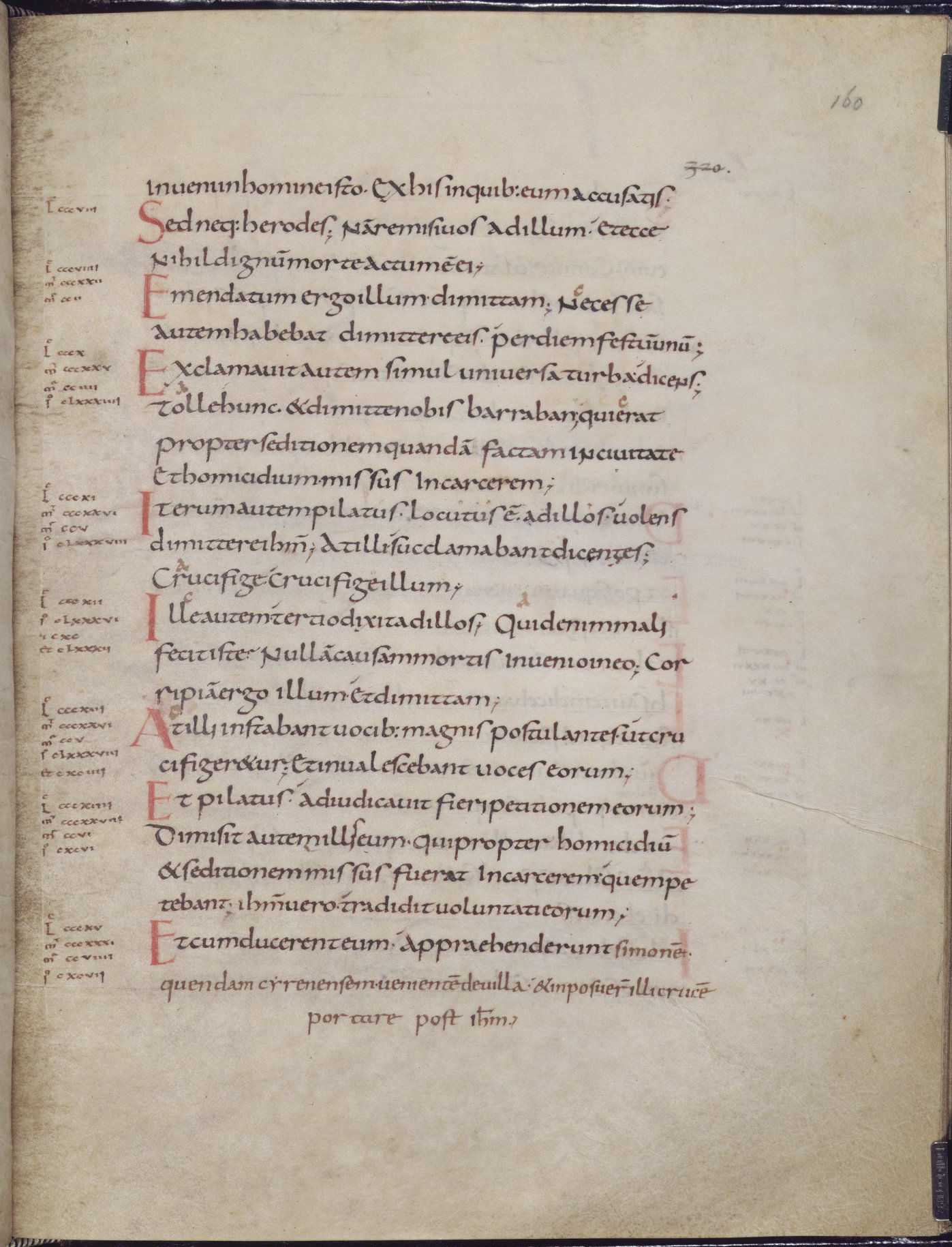

File:Karolingischer Buchmaler um 820 001.jpg, Aachen Gospels (c. 820), an example of Carolingian illumination.

File:St gall plan.jpg, A copy of the

The Carolingian Renaissance

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Matthew Innes, Julia Smith & Mary Garrison (''In Our Time'', Mar, 30, 2006) {{Authority control *

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances

The medieval renaissances were periods characterised by significant cultural renewal across medieval Western Europe. These are effectively seen as occurring in three phases - the Carolingian Renaissance (8th and 9th centuries), Ottonian Renaissan ...

, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lom ...

. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the Christian Roman Empire

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion. ...

of the fourth century. During this period, there was an increase of literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

, writing

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically Epigraphy, inscribed, Printing press, mechanically transferred, or Word processor, digitally represented Symbols (semiot ...

, visual art

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, filmmaking, design, crafts and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual art, and textile arts ...

s, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

, jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

reforms, and scriptural

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

studies.

The movement occurred mostly during the reigns of Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

rulers Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

and Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqui ...

. It was supported by the scholars of the Carolingian court, notably Alcuin of York

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

. Charlemagne's ''Admonitio generalis

The ' is a collection of legislation known as a capitulary issued by Charlemagne in 789, which covers educational and ecclesiastical reform within the Frankish kingdom. Capitularies were used in the Frankish kingdom during the Carolingian dynasty b ...

'' (789) and '' Epistola de litteris colendis'' served as manifestos.

The effects of this cultural revival were mostly limited to a small group of court '' literati''. According to John Contreni, "it had a spectacular effect on education and culture in Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

, a debatable effect on artistic endeavors, and an unmeasurable effect on what mattered most to the Carolingians, the moral regeneration of society". The secular and ecclesiastical leaders of the Carolingian Renaissance made efforts to write better Latin, to copy and preserve patristic and classical texts, and to develop a more legible, classicizing script, with clearly distinct capital and minuscule letters. It was the Carolingian minuscule

Carolingian minuscule or Caroline minuscule is a script which developed as a calligraphic standard in the medieval European period so that the Latin alphabet of Jerome's Vulgate Bible could be easily recognized by the literate class from one reg ...

that Renaissance humanists

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first Italian Renaissance, in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista ...

took to be Roman and employed as humanist minuscule

Humanist minuscule is a handwriting or style of script that was invented in secular circles in Italy, at the beginning of the fifteenth century. "Few periods in Western history have produced writing of such great beauty", observes the art histor ...

, from which has developed early modern Italic script

Italic script, also known as chancery cursive and Italic hand, is a semi-cursive, slightly sloped style of handwriting and calligraphy that was developed during the Renaissance in Italy. It is one of the most popular styles used in contemporary ...

. They also applied rational ideas to social issues for the first time in centuries, providing a common language and writing style that enabled communication throughout most of Europe.

Background

As Pierre Riché points out, the expression "Carolingian Renaissance" does not imply that Western Europe was barbaric or obscurantist before the Carolingian era. The centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West did not see an abrupt disappearance of the ancient schools, from which emerged

As Pierre Riché points out, the expression "Carolingian Renaissance" does not imply that Western Europe was barbaric or obscurantist before the Carolingian era. The centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West did not see an abrupt disappearance of the ancient schools, from which emerged Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

, Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' w ...

and Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

, essential icons of the Roman cultural heritage in the Middle Ages, thanks to which the disciplines of liberal arts were preserved. The 7th century saw the "Isidorian Renaissance" in the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic peoples, Germanic su ...

of Hispania in which sciences flourished and the integration of Christian and pre-Christian thought occurred, while the spread of Irish monastic schools (scriptoria

Scriptorium (), literally "a place for writing", is commonly used to refer to a room in medieval European monasteries devoted to the writing, copying and illuminating of manuscripts commonly handled by monastic scribes.

However, lay scribes and ...

) over Europe laid the groundwork for the Carolingian Renaissance.

There were numerous factors in this cultural expansion, the most obvious of which was that Charlemagne's uniting of most of Western Europe brought about peace and stability, which set the stage for prosperity. This period marked an economic revival in Western Europe, following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

. Local economies in the West had degenerated into largely subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow food crops to meet the needs of themselves and their families on smallholdings. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements, with little or no su ...

by the early seventh century, with towns functioning merely as places of gift-exchange for the elite. By the late seventh century, developed urban settlements had emerged, populated mostly by craftsmen, merchants and boaters and boasting street grids, artisanal production as well as regional and long-distance trade. A prime example of this type of emporium was Dorestad

Dorestad (''Dorestat, Duristat'') was an early medieval emporium, located in the southeast of the province of Utrecht in the Netherlands, close to the modern-day town of Wijk bij Duurstede.

It flourished during the 8th to early 9th centuries, ...

.

The development of the Carolingian economy was fueled by the efficient organization and exploitation of labor on large estates, producing a surplus of primarily grain, wine and salt. In turn, inter-regional trade in these commodities facilitated the expansion of towns. Archaeological data shows the continuation of this upward trend in the early eighth century. The zenith of the early Carolingian economy was reached from 775 to 830, coinciding with the largest surpluses of the period, large-scale building of churches as well as overpopulation and three famines that showed the limits of the system. After a period of disruption from 830 to 850, caused by civil wars and Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raids, economic development resumed in the 850s, with the emporiums disappearing completely and being replaced by fortified commercial towns.

One of the major causes of the sudden economic growth was the slave trade. Following the rise of the Arab empires, the Arab elites created a major demand for slaves with European slaves particularly prized. As a result of Charlemagne's wars of conquest in Eastern Europe, a steady supply of captured Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, Avars, Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

and Danes

Danes ( da, danskere, ) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

Danes generally regard t ...

reached merchants in Western Europe, who then exported the slaves via Ampurias, Girona

Girona (officially and in Catalan language, Catalan , Spanish: ''Gerona'' ) is a city in northern Catalonia, Spain, at the confluence of the Ter River, Ter, Onyar, Galligants, and Güell rivers. The city had an official population of 103,369 in ...

and the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

passes to Muslim Spain

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

and other parts of the Arab world. The market for slaves was so lucrative that it almost immediately transformed the long-distance trade of the European economies. The slave trade enabled the West to re-engage with the Muslim and Eastern Roman empires so that other industries, such as textiles, were able to grow in Europe as well.

Import

Kenneth Clark

Kenneth Mackenzie Clark, Baron Clark (13 July 1903 – 21 May 1983) was a British art historian, museum director, and broadcaster. After running two important art galleries in the 1930s and 1940s, he came to wider public notice on television ...

was of the view that by means of the Carolingian Renaissance, Western civilization survived by the skin of its teeth. However, the use of the term ''renaissance'' to describe this period is contested, notably by Lynn Thorndike

Lynn Thorndike (24 July 1882, in Lynn, Massachusetts, USA – 28 December 1965, Columbia University Club, New York City) was an American historian of medieval science and alchemy. He was the son of a clergyman, Edward R. Thorndike, and the younge ...

, due to the majority of changes brought about by this period being confined almost entirely to the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, and due to the period lacking the wide-ranging social movements of the later Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

.. Instead of being a rebirth of new cultural movements, the period was more an attempt to recreate the previous culture of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. The Carolingian Renaissance in retrospect also has some of the character of a false dawn, in that its cultural gains were largely dissipated within a couple of generations, a perception voiced by Walahfrid Strabo

Walafrid, alternatively spelt Walahfrid, nicknamed Strabo (or Strabus, i.e. " squint-eyed") (c. 80818 August 849), was an Alemannic Benedictine monk and theological writer who lived on Reichenau Island in southern Germany.

Life

Walafrid Str ...

(died 849), in his introduction to Einhard

Einhard (also Eginhard or Einhart; la, E(g)inhardus; 775 – 14 March 840) was a Frankish scholar and courtier. Einhard was a dedicated servant of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious; his main work is a biography of Charlemagne, the ''Vita ...

's ''Life of Charlemagne'', summing up the generation of renewal:

Charlemagne was able to offer the cultureless and, I might say, almost completely unenlightened territory of the realm which God had entrusted to him, a new enthusiasm for all human knowledge. In its earlier state of barbarousness, his kingdom had been hardly touched at all by any such zeal, but now it opened its eyes to God's illumination. In our own time the thirst for knowledge is disappearing again: the light of wisdom is less and less sought after and is now becoming rare again in most men's minds.

Scholarly efforts

A lack of Latin literacy in eighth-century western Europe caused problems for the Carolingian rulers by severely limiting the number of people capable of serving as court scribes in societies where Latin was valued. Of even greater concern to some rulers was the fact that not all parish priests possessed the skill to read theVulgate Bible

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels us ...

. An additional problem was that the vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin, also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin, is the range of non-formal Register (sociolinguistics), registers of Latin spoken from the Crisis of the Roman Republic, Late Roman Republic onward. Through time, Vulgar Latin would evolve ...

of the later Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

had begun to diverge into the regional dialects, the precursors to today's Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

, that were becoming mutually unintelligible and preventing scholars from one part of Europe being able to communicate with persons from another part of Europe.

To address these problems,

To address these problems, Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

ordered the creation of schools

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

in a capitulary

A capitulary (Medieval Latin ) was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since t ...

known as the ''Charter of Modern Thought'', issued in 787. Carolingian Schools, Carolingian Schools of Thought. A major part of his program of reform was to attract many of the leading scholars of the Christendom of his day to his court. Among the first called to court were Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

: Peter of Pisa

Peter of Pisa ( la, Petrus Pisanus; it, Pietro da Pisa; 744 – 799 AD), also known as Petrus Grammaticus, was an Italian grammarian, deacon and poet in the Early Middle Ages. In 776, after Charlemagne's conquest of the Lombard Kingdom, Peter was ...

, who from 776 to about 790 instructed Charlemagne in Latin, and from 776 to 787 Paulinus of Aquileia

Saint Paulinus II ( 726 – 11 January 802 or 804 AD) was a priest, theologian, poet, and one of the most eminent scholars of the Carolingian Renaissance. From 787 to his death, he was the Patriarch of Aquileia. He participated in a number of synod ...

, whom Charlemagne nominated as patriarch of Aquileia

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate (bishop), primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholicism, Independent Catholic Chur ...

in 787. The Lombard Paul the Deacon

Paul the Deacon ( 720s 13 April in 796, 797, 798, or 799 AD), also known as ''Paulus Diaconus'', ''Warnefridus'', ''Barnefridus'', or ''Winfridus'', and sometimes suffixed ''Cassinensis'' (''i.e.'' "of Monte Cassino"), was a Benedictine monk, s ...

was brought to court in 782 and remained until 787, when Charles nominated him abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The fem ...

of Montecassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first h ...

. Theodulf of Orléans

Theodulf of Orléans (Saragossa, Spain, 750(/60) – 18 December 821) was a writer, poet and the Bishop of Orléans (c. 798 to 818) during the reign of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. He was a key member of the Carolingian Renaissance and an im ...

was a Spanish Goth who served at court from 782 to 797 when nominated as bishop of Orléans

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

. Theodulf had been in friendly competition over the standardization of the Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels u ...

with the chief among the Charlemagne's scholars, Alcuin of York

Alcuin of York (; la, Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student o ...

. Alcuin was a Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

n monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

and deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

who served as head of the Palace School from 782 to 796, except for the years 790 to 793 when he returned to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. After 796, he continued his scholarly work as abbot of St. Martin's Monastery in Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 ...

. Among those to follow Alcuin across the Channel to the Frankish court was Joseph Scottus

Joseph or Josephus Scottus (died between 791 and 804), called the Deacon, was an Irish people, Irish scholar, diplomat, poet, and ecclesiastic, a figure in the Carolingian Renaissance. He has been cited as an early example of "the scholar in publi ...

, an Irishman who left some original biblical commentary and acrostic experiments. After this first generation of non-Frankish scholars, their Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

pupils, such as Angilbert

Angilbert ( – 18 February 814) was a noble Frankish poet who was educated under Alcuin and served Charlemagne as a secretary, diplomat, and son-in-law. He is venerated as a pre-Congregation saint and is still honored on the day of his dea ...

, would make their own mark.

The later courts of Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (german: Ludwig der Fromme; french: Louis le Pieux; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aqui ...

and Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (french: Charles le Chauve; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), king of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a ser ...

had similar groups of scholars many of whom were of Irish origin. The Irish monk Dicuil

Dicuilus (or the more vernacular version of the name Dícuil) was an Irish monk and geographer, born during the second half of the 8th century.

Background

The exact dates of Dicuil's birth and death are unknown. Of his life nothing is known exce ...

attended the former court, and the more famous Irishman John Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena, also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena, John the Scot, or John the Irish-born ( – c. 877) was an Irish Neoplatonist philosopher, theologian and poet of the Early Middle Ages. Bertrand Russell dubbed him "the most ...

attended the latter becoming head of the Palace School at Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

.

One of the primary efforts was the creation of a standardized curriculum for use at the recently created schools. Alcuin led this effort and was responsible for the writing of textbooks, creation of word lists, and establishing the trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ''De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but t ...

and quadrivium

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in the ...

as the basis for education.

Another contribution from this period was the development of Carolingian minuscule

Carolingian minuscule or Caroline minuscule is a script which developed as a calligraphic standard in the medieval European period so that the Latin alphabet of Jerome's Vulgate Bible could be easily recognized by the literate class from one reg ...

, a "book-hand" first used at the monasteries of Corbie

Corbie (; nl, Korbei) is a commune of the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

The small town is situated up river from Amiens, in the département of Somme and is the main town of the canton of Corbie. It lies ...

and Tours that introduced the use of lower-case letters. A standardized version of Latin was also developed that allowed for the coining of new words while retaining the grammatical rules of Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a literary standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used from 75 BC to the 3rd century AD, when it developed into Late Latin. In some later periods ...

. This Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

became a common language of scholarship and allowed administrators and travellers to make themselves understood in various regions of Europe.

Carolingian workshops produced over 100,000 manuscripts in the 9th century, of which some 6000 to 7000 survive. The Carolingians produced the earliest surviving copies of the works of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, Martial

Marcus Valerius Martialis (known in English as Martial ; March, between 38 and 41 AD – between 102 and 104 AD) was a Roman poet from Hispania (modern Spain) best known for his twelve books of ''Epigrams'', published in Rome between AD 86 and ...

, Statius

Publius Papinius Statius (Greek: Πόπλιος Παπίνιος Στάτιος; ; ) was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the ''Thebaid''; a collection of occasional poetry, ...

, Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

, Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (; – ), better known in English as Terence (), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 166–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought ...

, Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

, Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

and Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

. No copies of the texts of these authors were made in the Latin West in the 7th and 8th centuries.

Reform of Latin pronunciation

According to Roger Wright, the Carolingian Renaissance is responsible for the modern-day pronunciation ofEcclesiastical Latin

Latin, also called Church Latin or Liturgical Latin, is a form of Latin developed to discuss Christian thought in Late Antiquity and used in Christian liturgy, theology, and church administration down to the present day, especially in the Cathol ...

. Up until that point there had been no conceptual distinction between Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Romance

Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

* Romance languages, ...

; the former was simply regarded as the written form of the latter. For instance in early medieval Spain the word for 'century'—which would have been pronounced */sjeglo/— was properly spelled ⟨saeculum⟩, as it had been for the better part of a millennium. The scribe would not have read aloud ⟨saeculum⟩ as /sɛkulum/ any more than an English speaker today would pronounce ⟨knight⟩ as */knɪxt/.

Non-native speakers of Latin, however—such as clergy of Anglo-Saxon or Irish origin—appear to have used a rather different pronunciation, presumably attempting to sound out each word according to its spelling. The Carolingian Renaissance in France introduced this artificial pronunciation for the first time to native speakers as well. No longer would, for instance, the word ⟨viridiarium⟩ 'orchard' be read aloud as the equivalent Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

word */verdʒjǽr/. It now had to be pronounced precisely as spelled, with all six syllables: /viridiarium/.

Such a radical change had the effect of rendering Latin sermons completely unintelligible to the general Romance-speaking public, which prompted officials a few years later, at the Council of Tours

In the medieval Roman Catholic church there were several Councils of Tours, that city being an old seat of Christianity, and considered fairly centrally located in France.

Council of Tours 461

The Council was called by Perpetuus, Bishop of Tours, ...

, to instruct priests to read sermons aloud in the old way, in ''rusticam romanam linguam'' or 'plain roman espeech' (while the liturgy retained the new pronunciation to this day).

As there was now no unambiguous way to indicate whether a given text was to be read aloud as Latin or Romance, and native Germanic speakers (such as church singers) numerous in the empire might have struggled to read words in Latin orthography according to Romance orthoepy, various attempts were made in France to devise a new orthography for the latter; among the earliest examples are parts of the Oaths of Strasbourg

The Oaths of Strasbourg were a military pact made on 14 February 842 by Charles the Bald and Louis the German against their older brother Lothair I, the designated heir of Louis the Pious, the successor of Charlemagne. One year later the Treat ...

and the Sequence of Saint Eulalia

The ''Sequence of Saint Eulalia'', also known as the ''Canticle of Saint Eulalia'' (french: Séquence/Cantilène de sainte Eulalie) is the earliest surviving piece of French hagiography and one of the earliest extant texts in the vernacular langu ...

. As the Carolingian Reforms spread the 'proper' Latin pronunciation from France to other Romance-speaking areas, local scholars eventually felt the need to create distinct spelling systems for their own vernaculars as well, thereby initiating the literary phase of Medieval Romance. Writing in Romance does not appear to have become widespread until the Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, however.Wright 2002, p. 151

Carolingian art

Carolingian art spans the roughly hundred-year period from about 800–900. Although brief, it was an influential period. Northern Europe embraced classical Mediterranean Roman art forms for the first time, setting the stage for the rise ofRomanesque art

Romanesque art is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic Art, Gothic style in the 12th century, or later depending on region. The preceding period is known as the Pre-Romanesque period. The term was invented by 1 ...

and eventually Gothic art

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Northern, Southern and ...

in the West. Illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

s, metalwork

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on every scale ...

, small-scale sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s, and fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

s survive from the period.

Carolingian architecture

Carolingian architecture is the style of North European architecture promoted by Charlemagne. The period of architecture spans the late eighth and ninth centuries until the reign ofOtto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Francia, East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the olde ...

in 936, and was a conscious attempt to create a Roman Renaissance, emulating Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

, Early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

and Byzantine architecture

Byzantine architecture is the architecture of the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire.

The Byzantine era is usually dated from 330 AD, when Constantine the Great moved the Roman capital to Byzantium, which became Constantinople, until th ...

, with its own innovation, resulting in having a unique character. This syncretic architectural style can be exemplified by the first church of St Mark's in Venice, fusing proto-Romanesque and Byzantine influences.

There was a profusion of new clerical and secular buildings constructed during this period, John Contreni calculated that "The little more than eight decades between 768 to 855 alone saw the construction of 27 new cathedrals, 417 monasteries, and 100 royal residences".

Carolingian currency

Around AD 755, Charlemagne's fatherPepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

reformed the currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general def ...

of the Frankish Kingdom

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

.. A variety of local systems was standardized. Minor mints

A mint or breath mint is a food item often consumed as an after-meal refreshment or before business and social engagements to improve breath odor. Mints are commonly believed to soothe the stomach given their association with natural byproducts ...

were closed and royal control over the remaining bigger mints strengthened, increasing purity. In place of the gold Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

and Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

solidus

Solidus (Latin for "solid") may refer to:

* Solidus (coin), a Roman coin of nearly solid gold

* Solidus (punctuation), or slash, a punctuation mark

* Solidus (chemistry), the line on a phase diagram below which a substance is completely solid

* S ...

then common, he established a system based on a new .940-fine silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

penny

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is t ...

( la, denarius; french: denier) weighing 1/240 of a pound (', ', or '; '). (The Carolingian pound The Carolingian pound ( lat, pondus Caroli, german: Karlspfund), also called Charlemagne's pound or the Charlemagne pound, was a unit of weight that emerged during the reign of Charlemagne. It served both as a trading weight and a coinage weight. It ...

seems to have been about 489.5 gram

The gram (originally gramme; SI unit symbol g) is a Physical unit, unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI) equal to one one thousandth of a kilogram.

Originally defined as of 1795 as "the absolute weight of a volume of pure wate ...

s, making each penny about 2 gram

The gram (originally gramme; SI unit symbol g) is a Physical unit, unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI) equal to one one thousandth of a kilogram.

Originally defined as of 1795 as "the absolute weight of a volume of pure wate ...

s.) As the debased solidus was then roughly equivalent to 11 of these pennies, the shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

('; ') was established at that value, making it 1/22 of the silver pound. This was later adjusted to 12 and 1/20, respectively. During the Carolingian period, however, neither shillings or pounds were minted, being instead used as notional units of account.. (For instance, a "shilling" or "solidus" of grain was a measure equivalent to the amount of grain that 12 pennies could purchase.) Despite the purity and quality of the new pennies, however, they were repeatedly rejected by traders throughout the Carolingian period in favor of the gold coins used elsewhere, a situation that led to repeated legislation against such refusal to accept the king's currency..

The Carolingian system

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippi ...

was imported to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

by Offa of Mercia

Offa (died 29 July 796 AD) was List of monarchs of Mercia, King of Mercia, a kingdom of History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon England, from 757 until his death. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa of Mercia, Eowa, Offa came to ...

and other kings, where it formed the basis of English currency until the late 20th century.

Gallery

Plan of Saint Gall

The Plan of Saint Gall is a medieval architectural drawing of a monastic compound dating from 820–830 AD. It depicts an entire Benedictine monastic compound, including churches, houses, stables, kitchens, workshops, brewery, infirmary, and a ...

See also

*Iconography of Charlemagne

The rich iconography of Charlemagne is a reflection of Charlemagne's special position in Europe's collective memory, as the greatest of the Frankish kings, first Holy Roman Emperor, unifier of Western Europe, protector of the Catholic Church, prom ...

* Golden Age of medieval Bulgarian culture

The Golden Age of Bulgaria is the period of the Bulgarian cultural prosperity during the reign of emperor Simeon I the Great (889—927).Kiril Petkiv, The Voices of Medieval Bulgaria, Seventh-Fifteenth Century: The Records of a Bygone Culture' ...

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* . * * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * Panofsky, Erwin. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art. New York/Evanston: Harpers Torchbooks, 1969. * . * . * . * . * *External links

The Carolingian Renaissance

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Matthew Innes, Julia Smith & Mary Garrison (''In Our Time'', Mar, 30, 2006) {{Authority control *

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...